Metrical Patterns

Different tradition and genres of poetry tend to use different meters, ranging from the Shakespearian iambic pentameter and the Homeric dactylic hexameter to the Anapestic tetrameter used in many nursery rhymes. However, a number of variations to the established meter are common, both to provide emphasis or attention to given foot or line and to avoid boring repetition. For example, the stress in afoot may be inverted, a caesura (or pause) may be added (sometimes in place of a foot or stress), or the final foot in a line may be given a feminine ending to soften it or be replaced by a spondee to emphasize it and create a hard stop. Some patterns (such as iambic pentameter) tend to be fairly regular, while other patterns, such as dactylic hexameter, tend to be highly irregular. Regularity can vary between languages. In addition, different patterns often develop distinctively in the different language, so that for example iambic tetrameter in Russian will generally reflect a regularity in the use of accents to reinforce the meter which does not occur or occurs to a much lesser extent in English.

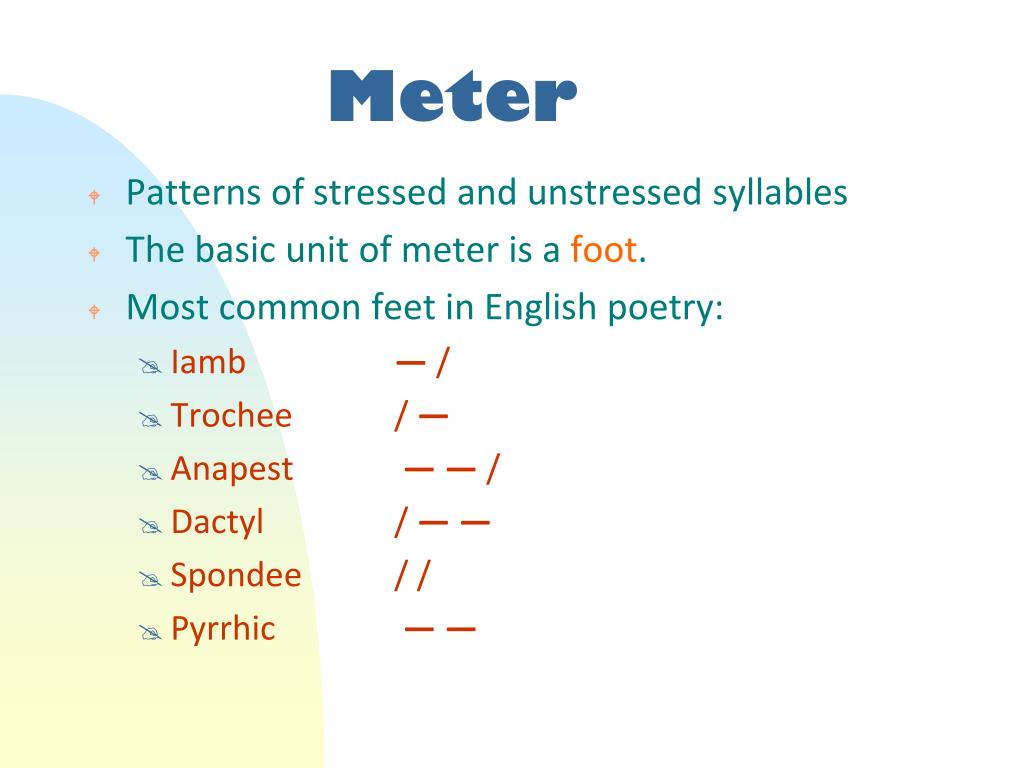

Some common metrical patterns, with the notable example of poets and poems who use them, include:

· Iambic pentameter ( John Milton, Paradise Lost )

· Dactylic Hexameter ( Homer, Iliad, Virgil, Aeneid)

· Iambic tetrameter ( Andrew Marvell, "To His Coy Mistress", Aleksandr Pushkin, Eugene Onegin)

· Trochaic octameter ( Edgar Allan Poe "The Raven"

· Anapestic tetrameter ( Lewis Carroll " The Hunting Of The Snark "; Lord Byron, Don Juan)

· Alexandrine ( Jean Racine, Phedre)

0 Comments